I’ve experienced many storms, including gales and hurricanes along the eastern seaboard and hail-filled thunderstorms with close-to-call tornados in Texas. And once, when I was on a boat crossing Lake Atitlan in Guatemala with a dozen other travelers, a sudden storm blew in with such intensity that we feared our boat might overturn.

One storm particularly was a gale that hit Money Island back in the 1970s.

Money Island, NJ is an area of the Delaware Bayshore, described by author Andrew Lewis to be ‘where some 85,000 acres of Spartina meadows roll to the lapping edges of the brown Delaware Bay.”

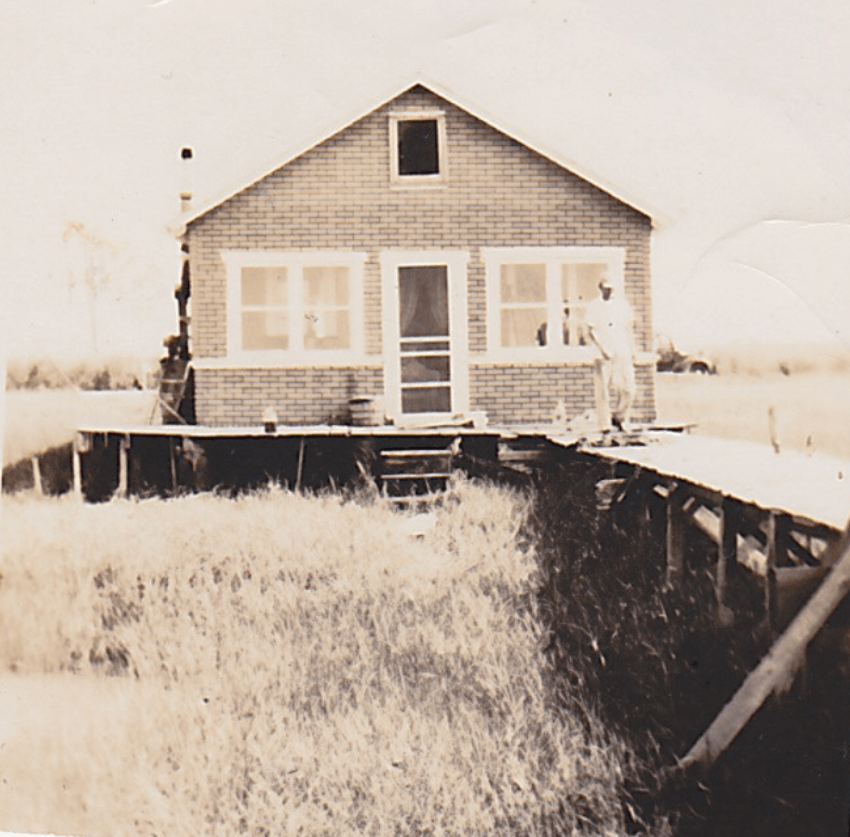

My Aunt Sis and Uncle Reds spent their Summers on Money Island throughout most of their lives. They bought a house on Money Island back in the 1940s-1950s. Their son, Jack (my Uncle) and my mother, when they were kids, would run up the gravel road to the marina to buy ice cream. They loved going to the end of the pier to fish or catch crabs.

Jack’s father, Reds (1940s)

Decades later in the 1970s, when my family returned to New Jersey after several years in Maine, Sis and Reds were now living in a mobile home because their original house had been destroyed by a storm. This new home sat on fixed pilings. These pilings extended far enough into the bay so that two-thirds of their home was suspended above the high tide mark. You had to walk a boardwalk—or ‘gangplank’ as we liked to call it—to get to their front door, because at high tide, the bay was under the boardwalk.

Our experiences at Money Island were a little different from my mother’s. I used to think of it as ‘muddy island.’ I saw a wide open stretch of sandy marshland with a small marina, followed by a row of cheaply built dwellings existing very close to the edge of the bay. The area often smelled like marsh and the beaches had lots of horseshoe crabs. If the winds were blowing in the wrong direction, you would be bitten repeatedly by large green-head flies that left welts on your skin.

We liked to walk around the beach and marsh areas, exploring the tidal pools which were warm like bath water, while avoiding the nesting crabs. We didn’t want to injure them and we were also freaked out by them. Horseshoe crabs aren’t even true crabs. They’re chelicerates which make them more closer to arachnids (think spiders and scorpions).

The pier at Sis and Red’s home extended far enough out into the bay that there was always water below, even at low tide. Here we would try to catch blue crabs. Crabbing is where you take a metal crab trap—a box where the 4 sides fold out—and suspend it from pier with a light rope. Chopped scraps of chicken, fish, or squid are fastened to the bottom of the trap. You wait for the crab to go after the bait and then pull the rope up with the sides of the box closing around the crab.

Because I couldn’t see the ground clearly through the water, I used to think there must be tens of crabs just sitting there at the bottom of the pier, hanging out in wait. This thought, coupled with the murkiness of the water, meant that I would never swim in the water off the pier. Once when I was playing on the ladder there that dropped into bay, I slipped and fell in. I shrieked, thinking that I would step into a mass of crabs, but there were none.

We’d usually see my Uncle Jack there and we’d go boating or fishing with him.

The Storm

One evening, a storm blew in. We had been sleeping on bunks in one of the rooms. Winds continued to intensify and hit the sides of the mobile home. It was one of these slamming sounds that woke me up. I heard hushed anxious voices and smelled cigarette smoke drifting down the hallway—and all of the lights were out. I walked down the hall toward the kitchen and saw them all—my mother, her husband Bob, and Sis and Reds—hovering over a large marine radio, listening to storm reports. My mother saw me and told me to go back to bed. Her voice had a concerned tightness.

I lie in bed for the next hour thinking about how it had been high tide when the storm started. I could hear the Delaware bay running under the metal floor. I wondered how high the water would have to rise before it could displace the weight of the structure—and carry it off the pilings. Would the storm hoist this house trailer into the deepness of the bay like a tin can? Would we drown with 8 people trying to clamber out the tiny door? The windows are so small. Should I wake up my siblings so we could be ready just in case?

My mother walked by the room. ‘Is it going to be ok?’ I called. ‘Yes, go to sleep. It’s ok.’

About 15 minutes later, the winds began to die down. The rain fell more lightly. I stopped hearing the water under the floor. I fell asleep.

Within the next decade that followed, my aunt and uncle lost two mobile homes to storms. We had been lucky that night.

Now more decades later, there are no dwellings on that lot nor the ones nearby. Only the pilings remain. Hurricane Sandy, which made the gale I experienced seem like a light breeze devastated most of the area in 2012.

The Delaware Bayshore area has become one of the most vulnerable areas on the eastern seaboard due to the threat of climate change. There are far fewer horseshoe crabs and there are fewer Red Knots to eat them.

Leave a comment